It's been awhile since I've made a new post, but I've got some ideas floating around I thought I'd throw out there to see if they're totally ludicrous or not. So here goes.

The genesis of these ideas lies in Michaelyn Podany's AP Biology with my lovelies, John Massengale and Tara Westlund, sometime in March 2007. A month away from the AP exam, we discussed biological feedback systems, which as far as I understand fall into two main categories: negative feedback systems and positive ones.

Negative feedback systems maintain "homeostasis," a fancy way of saying balance. In a negative system, two or more influences oppose each other to keep the system at equilibrium. The body's internal thermostat is a good example of a negative feedback system: if internal temperature starts rising, the body starts sweating because evaporating water molecules off of the skin carry heat away, cooling the body back down.

Positive feedback systems have the opposite effect. Two or more influences in a positive system amplify one another in a kind of "vicious cycle": one influence intensifies a second, which in turn intensifies the first. In Podany's class we used the example of childbirth: contractions produce oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates more contractions, which in turn stimulates the production of more oxytocin, creating more contractions, and so on.

Hang on to this idea of positive feedback while I explain a second phenomenon. The next step in my logic comes from relations between the nobility and the upper-crust of bourgeois society in French society of the 17th and 18th centuries.

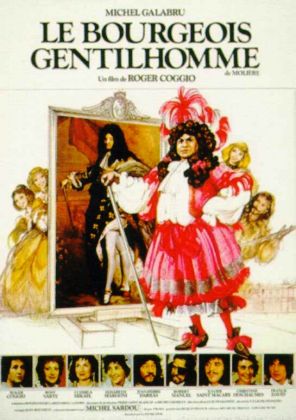

Back in the good old days before 1789, French society was divided into three "estates": the nobility, the clergy, and the tiers état, a catchall for everyone who didn't fit into the first two groups. Under the feudal system, that third estate was mostly comprised of peasants, artisans and city dwellers (the bourgeoisie, which word shares a common ancestor with our -burg as in Pittsburg). For a long time, this class looked nothing like the first two, namely lacking the manners and spending power of the nobility and the clergy. However, over time, members of the bourgeoisie grew increasingly wealthy and began to (try to) model themselves on the aristocracy. Molière actually wrote a play called Le Bourgeois gentilhomme ridiculing this class's attempts to imitate the nobility, acquiring the latter's decadent tastes but not its refined manners. "But, at bottom, everyone above the masses resembled one another; they had the same ideas, the same habits, the same tastes, were inclined to the same pleasures, read the same books, spoke the same language," wrote Alexis de Tocqueville in his analysis The Old Regime and Revolution. "The only difference was in their rights."

The point to retain from this bit is that as the more exposure the bourgeoisie had to the nobility, the more the top of the third estate came to resemble the aristocracy, and the more economic clout they gained, the more aware they became of the inequality of their disadvantaged political situation. Nothing, they felt, divided them from the nobility except some silly titles and privileges bestowed by medieval monarchs - and even those had since been commodified, up for sale to rich members of the bourgeoisie.

In this I want to stress that the Revolution sprang from the third estate's realization that it wasn't so different from the privileged classes. 1789 would have been totally unfathomable under the feudal system in which the first and third estates looked so different. When the bourgeoisie started to resemble the aristocracy, they realized they were missing something.

What I'm getting at is this: you can't want something unless you feel its lack. In order to desire something, you have to realize that you don't have it.

Pascal says something similar in his Pensées. "For who is unhappy at not being a king, except a deposed king? . . . Who is unhappy at having only one mouth? And who is not unhappy at having only one eye? Probably no man ever ventured to mourn at not having three eyes. But any one is inconsolable at having none." (409)

In the case of the bourgeoisie, they realized over time that compared to the nobility, that in terms of political rights they had "only one eye" while the nobility had two.

Okay. Are you still with me? Let's recap the two essential ideas I wanted to distill here:

(1) The "vicious cycle" principle: in systems of positive feedback, two influences reinforce and amplify one another.

(2) The "

big yellow taxi" principle: in the oft-repeated words of Joni Mitchell, "you don't know what you've got 'til it's gone." Because humans can get used to just about anything, we have to be made aware of what we lack, and as in the case of the French bourgeoisie, that comes with exposure to people who resemble us, except in one (or a few) glaring ways.

I think these two ideas, used in conjunction, might be useful in approaches to women's history. It is probably not very useful or enlightening to look back at history aiming to condemn the past's "misogyny." I certainly don't mean that by today's standards lots of practices, laws, and attitudes were not discriminatory to women. I also do not mean that those discriminatory practices, laws, and attitudes are in any way justified. Instead, I think it is important to realize that our ideas about gender parity are products of gradually increasing rights and mobility and increasing awareness.

What I mean is this. In French history, the third estate had always been aware that it was "different" from - that is, "inferior" to - the nobility, contrived as that difference and inferiority was. It was only with increased power and growing resemblance to the nobility that the third estate recognized its unjustified lack.

In the same way, women have been recognized as distinct from - very often meaning in contemporary contexts "inferior" to - men. But do you think a woman in 18th century England saw herself as a man's equal? Do you think she thought herself capable of becoming prime minister? a doctor? a professor? the next Newton? I would argue not. Why do girls today see those possibilities open to them? Because of a continually expanding circle of possibilities.

Gender parity is a positive feedback system. Little by little, expanding influence made for expanding rights, which made for expanding influence, and again expanding rights. Women gained access to universities, the coming generations saw professors, then department chairs, then university presidents. Opening opportunities to women made (and makes) them think differently about themselves and push for more opportunities.

I do want to point out that in studying women's history, it is important to recognize this process and thus that an era may not have even been aware of its gender discrimination. That means to me that we should be less concerned with reproving the gender paradigms of the past by our own standards and more concerned with how women operated within their contemporary paradigms of gender relations. The first attitude makes the fatal mistake of considering contemporary thought the teleological end of all previous thought: "No one has gotten it totally right until today!" but forgetting that tomorrow's thought will likely be revising today's, too.

... which always makes me wonder what the next generations will think about our contemporary paradigms. "How backwards society was at the turn of the 21st century!" What are we not yet aware of? What positive feedback systems are in the works?

This week for my political philosophy class I read, for the first time in full, the Communist Manifesto. And, don't tell Joseph McCarthy (or the Tea Party or my politicalphilosophy professor) but I actually kind of liked it. Or liked parts of it. What's most intriguing to me about the Manifesto is that it presented a different way of reading history.

This week for my political philosophy class I read, for the first time in full, the Communist Manifesto. And, don't tell Joseph McCarthy (or the Tea Party or my politicalphilosophy professor) but I actually kind of liked it. Or liked parts of it. What's most intriguing to me about the Manifesto is that it presented a different way of reading history.